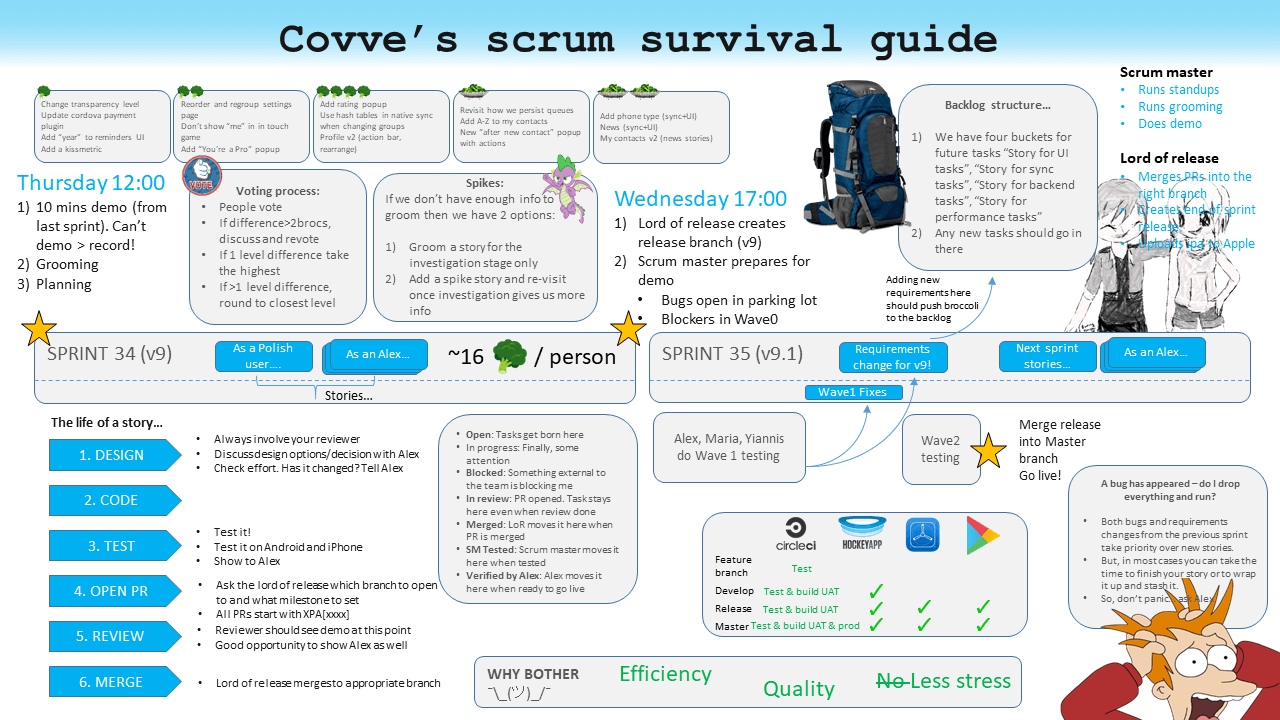

Scrum seems to be the default methodology in software engineering, especially when it comes to startups. However, getting from the simple, shiny theory to a detailed process that survives the messy, chaotic and unpredictable real world is another matter. So, after four years of fine tuning, adjusting and debating, I’m glad to present Covve’s scrum survival guide (in the form of a badly made infographic).

In this post I’ll set out the issues we faced when implementing scrum at Covve, the options we considered and the decisions we made. It’s not about describing what scrum is but rather how we tweaked and changed to make it work for our team. Whether or not it works for yours is another matter! The process described here uses our cross-platform app project as an example but the same process and principles apply to our other teams too.

What’s the point

For people who haven’t worked with scrum before it can appear quite daunting. They may be tempted to think it adds unecessary overhead to their day as well as a bunch of seemilngly long and tedious meetings. I can wax lyrical about all the goodness that scrum brings to our company, team and product but I’ll summarise in three points:

The basics

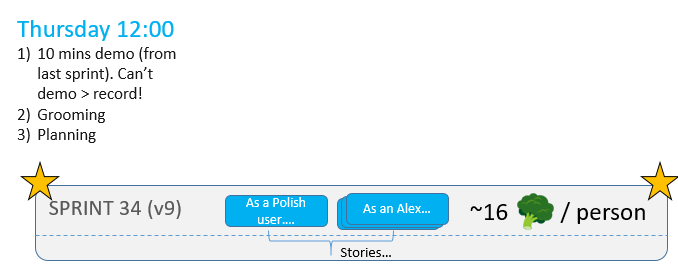

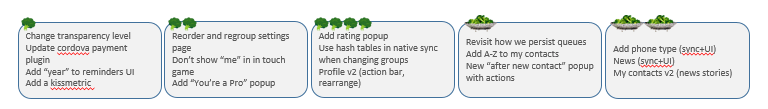

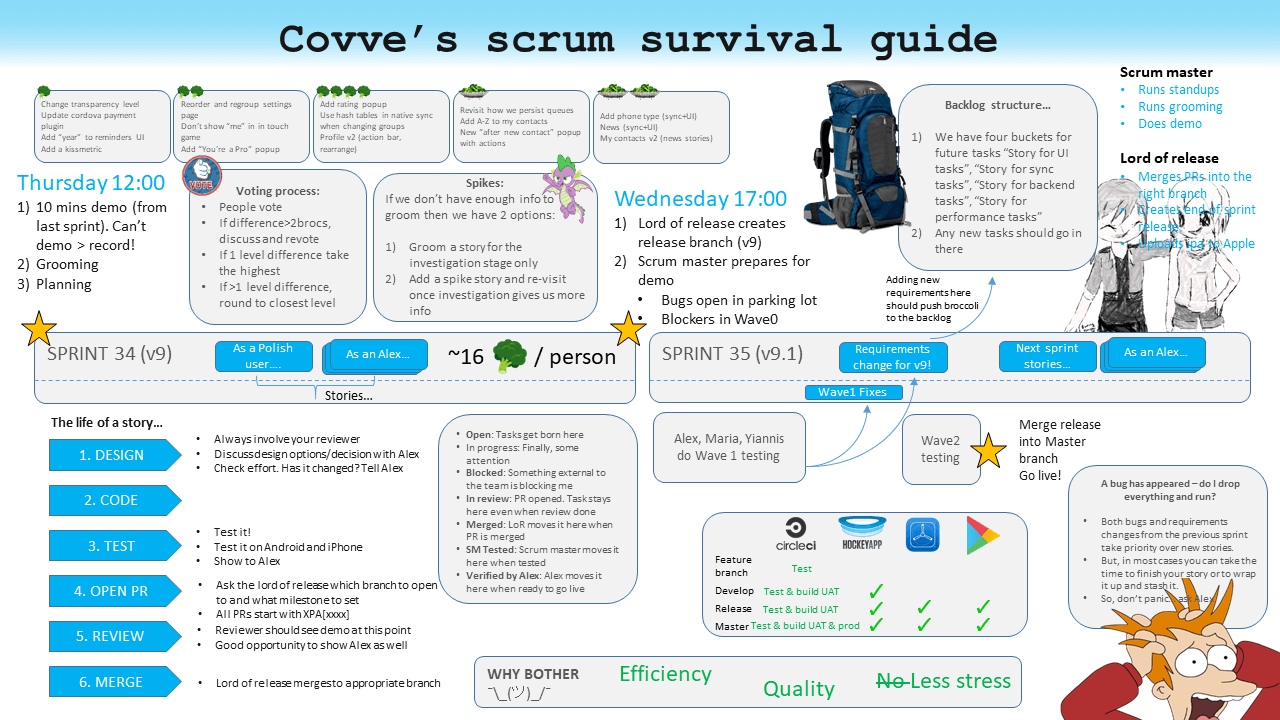

Our sprints last two weeks each. In each sprint:

- We start with a demo of the work completed in the sprint just finished

- We then proceed with grooming our stories (assigning Broccoli to stories, more on this in a sec) and planning the next two weeks

- During the sprint the team works on the assigned stories as well as fixes on last sprint’s version as well as other tasks (from supporting users to participating in workshops)

- At the end of the sprint, at 5pm on Wednesday, the release train leaves (more on this later)

About broccoli and other decisions

The effort/size of a story is typically measured in story points. Story points are boring though so our team measures stories in broccoli, a vegetable our team isn’t too fond of, so, the more broccoli a story has, the harder it is!

After running the process for a few months we established that our team delivers around 16 broccoli per person and created a “menu” of sample stories and their broccoli to help us estimate going forwards. Also, we concluded on using powers of two as the allowable number of broccoli for a story (i.e. 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 broccoli)

Three specific points of debate relating to broccoli:

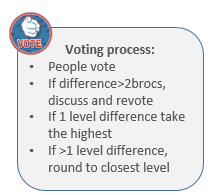

Consensus

When estimating the broccoli for a story, all team members vote simultaneously. If all hands show the same number then that’s the estimate we use. If on the other hand there are differences some kind of consensus needs to be reached. The balance here is between getting as good an estimate as possible (and shedding light on assumptions people make or relevant knowledge they have) and keeping the grooming session to a reasonable length. As such we’ve decided that:

- If the difference is <3 broccoli (between the highest and lowest estimate) then we just take the higher estimate

- If the difference is >3 broccoli then people explain and debate and a further round of voting takes places

- At this point we take the average and round to the closest number

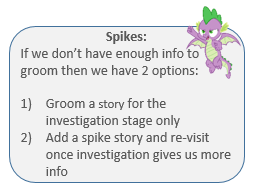

Spike stories

Sometimes its just not possible to estimate a story. This is usually because there are too many unknowns (e.g. using technologies we’ve never used, or integrating with 3rd parties we’ve never investigated). These are called spike stories. We deal with them in two ways:

- Create a smaller story solely for the investigation necessary to remove the unknowns. This may include research, a proof of concept and/or design work

- Alternatively we accept the story as a spike (i.e. no estimate) and make sure to revisit shortly after work starts on the story

Assigning stories to people

In theory, a team is comprised of roughly equivalent people. This implies that anyone can deliver any story and that the team works as a unit with people being interchangeable - when a developer finishes a story they just grab the next one on the team’s list. Well, practice couldn’t be further away. Each person has different knowledge, different experience and has worked on specific aspects of Covve up to now. If, say, Nikos has written the app’s Android contacts sync plugin, he’ll be much better equipped than any other person to make changes to this plugin.

Which leads us to whether stories should have specific people assigned to them. Given the above, for our team, we decided that yes, they should. At the planning stage each story gets an owner who is responsible for delivering it. This allows each person to understand what they’ll be working on the next two weeks and plan accordingly. The owner is likely to involve other people in various stages of the story but will remain the person responsible throughout.

The Master and the Lord

Each sprint has two roles who rotate amongst the team:

- The Scrum Master who does the usual scrum-master-y things but also is in charge of the end-of-sprint demo

- The Lord of Release who is responsible for knowing and controlling which pull request merges into which release and for making sure the right build processes are run at the right times. This role requires both good knowledge of our business plans and pipeline and also a good grasp of our Continuous Integration and devops.

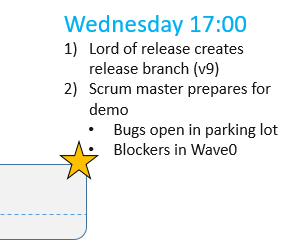

Choo choo… the end of the sprint

At 5pm every second Wednesday there’s always a flurry of activity in the office and on Slack. At 5pm a new release branch is borne, including all the stories which were DoneDoneDone in this sprint. At this point a sequence of events kicks off:

- The Lord of Release merges any final pull requests (as long as they’re DoneDoneDone) and creates the release branch.

- The Scrum Master will do a dry run in advance of tomorrow’s demo. This is a great opportunity for identifying any integration issues which may have crept in between pull requests as well as identify any bugs against the stories’ requirements.

- If small bugs are found they are added to our “Testing parking lot”. If a blocking issue is identified (e.g. app doesn’t load!) then we open the very first story of the new sprint called “Testing Wave 0 bugs”. The relevant people work on these blocking issues immediately, aiming to resolve in time for the next day’s demo

- At midday on Thursday we demo the new release and start the new sprint (with grooming and planning)

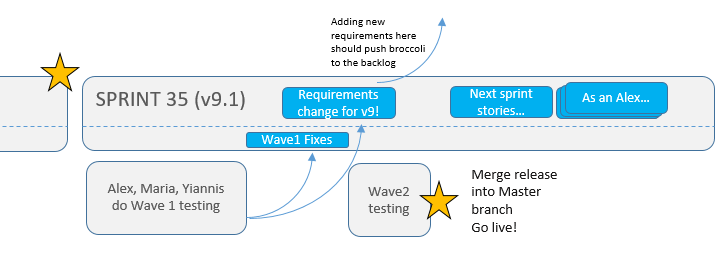

The sprint within the sprint

A sprint sounds like such a tidy and shiny thing. It starts with a blank sheet and gets filled with just the right stories. Everyone then works with laser focus on just these stories. Sounds great.

And then at around 1 minute into a nice fresh sprint the panic starts: bugs identified in testing the previous sprint’s release, tweaks to designs and requirements, support for users, ad-hoc investigations, participation in workshops… the list goes on. To help structure things, we’ve found the following process works well:

- At the end of a sprint the new release is created (lets call it v9.0)

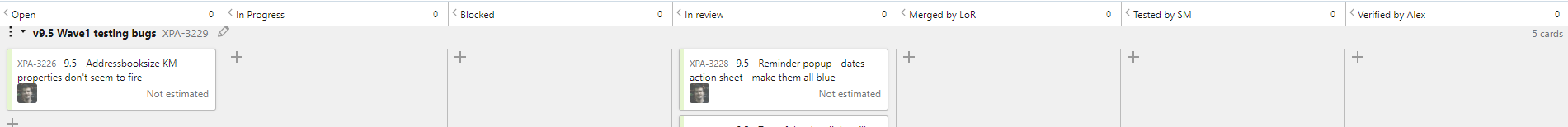

- While the team are starting the next sprint (which will, in two weeks, deliver v9.1), the people responsible for testing will start testing v9.0. We call this “Wave 1 testing”

- We make sure that no bugs/tasks are added to the board until all of Wave1 testing has completed. This avoids the disruption of bugs appearing one at a time

- When Wave1 is complete, then a “v9.0 Wave 1 testing” story gets added to the board. Wave1 testing tasks take priority over the stories planned into the sprint. Bugs that are identified at this stage typically relate to testing which is larget than the scope of a single story (single stories are tested before they are merged). This includes complex integration scenarios, multi-language support, deployment on different mobile operating systems and so on.

- Once the fixes are made, the Lord of Release will create a new version which will then undergo Wave 2 testing and, if need be, Wave 2 fixes

- Testing (which includes our QA lead, UX lead, Customer Success, and CTO) may also reveal the need to make changes to designs, requirements or implementation. Being an agile team in a startup, means that we seek feedback and iterate very often, which means that we may need to tweak behaviour and experience even during development. In this instance, being pragmatic and raising these changes as they appear is more important than being purist and waiting until the next sprint to address. Such changes are not marked as bugs, but rather added as priority stories to the board. They are estimated and the same number of broccoli are removed from the board to make sure the total remains the same

A stress-free approach to releasing to production every two weeks

In order for the scrum process to pay off, it needs to be supported by specific tools and processes. There are three things that make it possible for us to release a new version of our app every two weeks with minimal stress and risk:

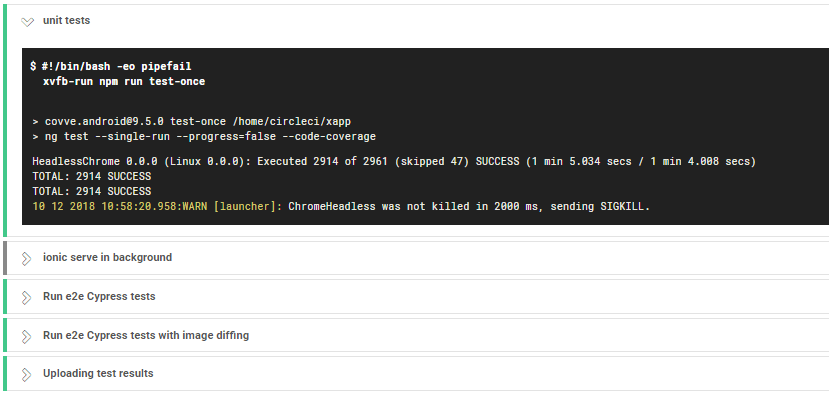

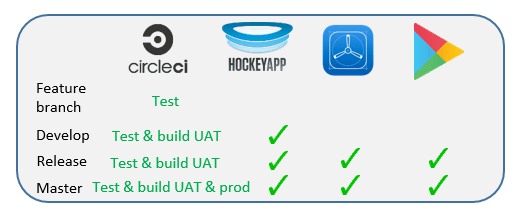

- Automatic tests: Over 4000 unit tests run each and every time our code is built. On top of that, automatic end to end tests run on every build of a release branch, simulating the behaviour of users, navigating and interacting with the app and taking screenshots along the way. If anything is different or looks suspicious, an alert is raised

- Continuous Integration: For our team to be able to rapidly develop, and release with confidence we have invested heavily in automating every aspect of the build process. This means that from merging a pull request into our repo, all the way to releasing on the app stores, the only human intervention is pressing the “Release” button on iTunes and Google Play

-

Process: Having tried the usual “no bugs allowed from Monday” memo, we’ve tuned our process to include the right steps that encourage and promote quality, including:

- Ensuring new code has sufficient test coverage

- Every single commit must pass review from another team member

- The review process also includes a mini-demo. Demonstrating the new features on a physical device (as opposed to, say, the iPhone simulator). If this is not practical (e.g. because setting up the conditions for the demo would take too long), then the developer shows a recording of the code in action

- At the end of the sprint the Scrum Master will do an initial round of testing in preparation for the demo the next day

- Our testing team, which includes QA, UX, customer success and our CTO and CEO will then test the new version (each from their own perspective and with their own brief)

- We’ll then release the version in Beta and see how it likes the real world

Aligning Github and our scrum board (Jet Brains’ YouTrack)

Our two main tools throughout this process is Github and our scrum board (we happen to use YouTrack). Each of these has its own statuses and is used at different parts of a story’s lifecycle:

- The scrum board is higher level and represents the story from inception to release. We use special statuses to indicate when a story has “left” the developer and is in the review process, when the story’s been merged by the Lord of Release, when its been tested by the Scrum Master and so on.

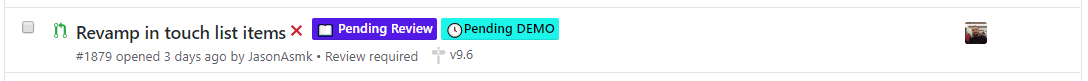

- Github is used to manage the states of a story/pull request from the point of the PR being created and sent for review until the point when it is merged by the Lord of Release. This includes micro-statuses such as “Comments resolved” and “Demo pending”

Bringing it all together

We’ve invested heavily in making our engineering process as clear, repeatable and reliable as possible. This has included a lot of CI automation and a lot of tweaks to the process itself. And it’s paying off. Our team delivers consistently, efficiently and at high quality despite operating in the maelstrom which is the startup world. With everything changing every day, urgent issues and opportunities arising and innovation being at the heart of what we do, our scrum process is an oasis of calm, consistency and efficiency.

For me that’s a big success.

Comments